The portraiture of Valentin Serov.

In today’s blog I want to look at another artist who has many of his works of art featured in the Tretyakov Gallery, including a number of portraits. Let me introduce you to Valentin Alexandrovich Serov who was a Russian painter, and one of the leading portrait artists of his era.

Valentin Alexandrovich Serov was born in St Petersburg in 1865 and was to become one of the foremost portrait artists of his time. He was the only-child of Alexander Nikolayevich Serov and his wife, Valentina Serova née Bergman. His father Alexander was a Russian composer and one of the most important music critics in Russia during the 1850s and 1860s.

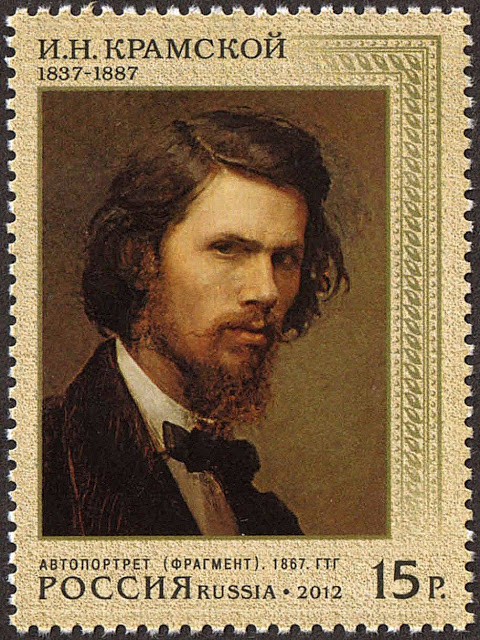

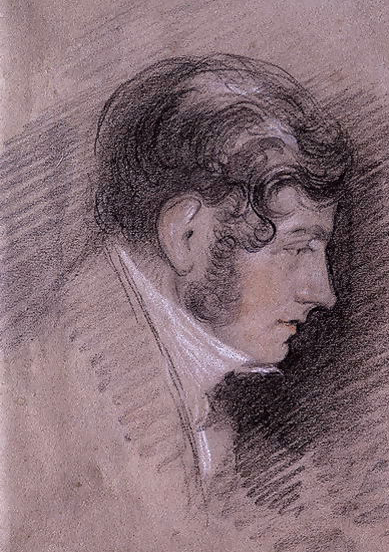

His mother, Valentina had studied for a short time at the St. Petersburg Conservatory with Anton Rubinstein but left to study with Alexander Serov whom she married in 1863. Valentin Serov was brought up in a musical and artistic household. At the age of six his father died from a heart attack and his mother sent him to live with a friend in a commune in Smolensk province and later he accompanied his mother on her travels throughout Europe as she sought to further her musical career. In 1874 mother and son arrived in Paris where they met Ilya Repin who took the nine-year-old Valentin under his wing and gave him daily drawing lessons. In 1880 Repin arranged for Valentin to attend and study art for five years at the St Petersburg Academy of Arts under Pavel Chistyakov. Serov was very interested in the Realism genre of art and was greatly influenced by what he saw in the major galleries and museums of his home country and those of Western Europe.

In 1874, Repin introduced Valentin Serov and his mother to Savva Mamontov the railroad tycoon and entrepreneur, philanthropist, and founder and creative director of the Moscow Private Opera. Mamontov was best known for supporting a revival of traditional Russian arts at an artists’ colony he led at Abramtsevo. On returning to Moscow from Paris, he and his mother were invited by Savva Mamontov to settle at Abramtsevo, an estate located north of Moscow, on the Vorya River. This estate had become a centre for the Slavophile Movement, an intellectual movement originating from the 19th century that wanted the Russian Empire to be developed upon values and institutions derived from its early history.

Abramtsevo was originally owned by the Russian author Sergei Akaskov. On his death the property was purchased by the wealthy railroad tycoon and patron of the arts, Savva Mamontov. Through his efforts, Abramtsevo became a centre for Russian folk art and during the 1870’s and 1880’s the estate was to be home for many artists who tried to reignite the interest, through their paintings, in medieval Russian art. Workshops were set up on the estate and production of furniture, ceramics and silks, ablaze with traditional Russian imagery and themes, were produced. It was during his time here that Serov came into contact with the cream of Russia’s artistic and cultural talent.

Portraiture can come in a number of forms. Portraits can look official, stiff with a muted background so as not to detract from the aura of the sitter or they can be gentler and loving, often depicting family members. To start with let me show some of Serov’s more “natural” portraiture. One of my favourite works by Serov, and probably his best known, is his 1887 work entitled Girl with Peaches. Portrait of V.S. Mamontova which is housed in the Tretyakov Gallery. It was during his time at the Abramtsevo Colony, that Valentin Serov met and painted the portrait of Vera Mamontov, the twelve-year-old daughter of Savva Mamontov. Some believe that this work launched Russian Impressionism. Serov exhibited this painting at the Academy of Fine Arts, St Petersburg and received great acclaim and it is now looked upon as one of his greatest works. The painting which hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow is a more relaxed study and is breathtakingly beautiful. In the centre of the painting, we see depicted a portrait image of Savva’s Mamontov’s eldest daughter Vera. Serov was fascinated by the young girl who he looked upon as the little “Muse” of the Abramtsevo circle. The painting is a mixture of portraiture, fragments of interior, landscape, still-life which Serov combined in this beautiful work. The light shines through the window behind the girl and she is depicted using warm tones, which contrast with the cold grey tones of the space around her. The black eyes of the girl look out at us, thoughtful but slightly impatient at the length of time she had to pose for Serov and the number of sittings she had to endure. Valentin Serov knew Vera Mamontova from when she was born as he was a regular visitor to Mamontov’s Abramtsevo estate, and on a number of occasions he would live there for long periods. Serov would later recall painting this picture:

“…All I wanted was freshness, that special freshness that you can always feel in real life and don’t see in paintings. I painted it for over a month and tortured her, poor child, to death, because I wanted to preserve the freshness in the finished painting, as you can see in old works by great masters…”

During the 1880’s Serov travelled abroad and came into contact with French Impressionism and the Impressionist painters such as Degas. Due to his family background and the popularity of his paintings, Serov never struggled financially. He was the foremost portraiture artist of his time and his subjects included Emperor Nicholas II.

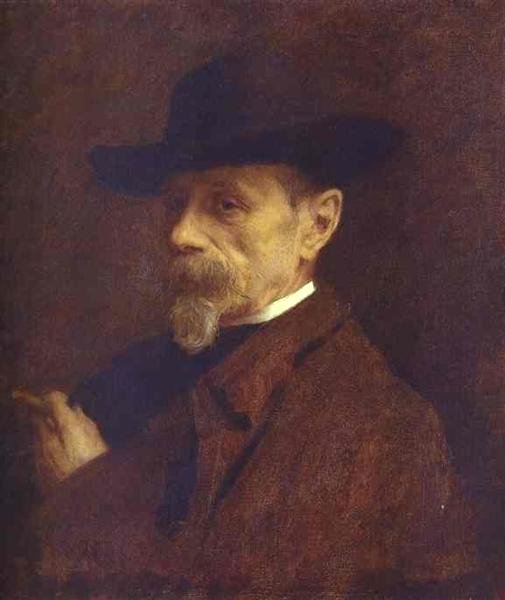

In 1887, after knowing each other for many years, Valentin Serov married Olga Feerovna Trubnikova and one of the witnesses at the wedding was Ilya Repin. Serov completed a watercolour portrait of his friend and one-time mentor Repin in 1901. It is now to be seen at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Olga was a quiet lady and was once described as a petit, pleasant blonde with beautiful eyes, simple and very modest. She was the ideal wife for Serov. She was supportive, a sympathetic listener who and would listen to her husband’s grand plans for his artistic future. In a letter to his wife dated May 1887 he talked about his love of the Impressionist’s lifestyle writing:

“…I want to be just as carefree. At present they all paint heavily without joy. I want joy and will paint joyfully…”

Olga Serova featured in many of his paintings. One example of this is his 1886 work entitled By the Window. Portrait of Olga Trubnikova.

Serov completed another more famous portrait of his wife in 1895 entitled In Summer. In this work we see Olga in the foreground and in the background one can see Olga and Yuri, two of their children, playing in a field in the village of Domotkanovo, at the country estate of Serov’s former schoolfriend and fellow Academy of Arts student, the watercolourist, Vladamir Derviz. Derviz had bought the estate with his inheritance from his father, a St. Petersburg senator. Serov often stayed on the estate as, for him, it was a welcome relief to get away from the large city of Moscow and the professional networking he had to endure to secure commissions. It is a modest depiction of great charm. It is a plein air painting which really captures the qualities of the light. The painting is full of silver-greys and muted green, blue and white colours. Olga’s dress is a mixture of pale pink, a hint of gold and blueish lilac colours.

Another of Serov’s female portraits was of his cousin, Maria Simonovich, entitled Girl in the Sunlight which he completed in 1888. His cousin remembered the long plein air sittings for the painting, writing:

“…He was looking for new ways to transfer to the canvas infinitely varied play of light and shade while retaining the freshness of colours. Yes, I sat there for three months, and almost without a break…”

During one of his stays at the Domotkanovo estate of Vladamir Derviz, Serov completed a portrait of his host’s wife, Nadezhda with her young child. Nadezhda was Serov’s cousin. The painting entitled Nadezhda Dervi with Her Child is dated 1888-1889 but is unfinished. It was experimentally painted on an iron roofing-sheet, presumably purchased for the replacement of the old wooden lath roof of the Domotkanovo house with a new one. Serov initially started painting this portrait in 1887 when baby Maria was a breastfed baby and Serov continued with the painting a year later when baby Maria had become too big.

Art needs artists. Artists need commissions. Commissions come from wealthy patronage. In the late nineteenth-century many of the Russian patrons were wealthy industrialists. A prime example of this was the Morozov family. Savva Vasilyevich Morozov was the eighteenth-century entrepreneur, who founded the Morozov dynasty of entrepreneurs. Two of the descendants from this ultra-wealthy family were the brothers, Ivan and Mikhail Morozov, both art collectors and patrons of the art. Ivan, a major collector of avant-garde French art, was known for his patronage of both the theatre and visual arts and was a painter himself. Ivan Morozov had a passion for paintings by Matisse and in Serov’s 1910 portrait of Ivan Morozov we can see Matisse’s 1910 painting, Fruit and Bronze which the industrialist had acquired that year.

Ivan’s brother Mikhail was also featured in a Serov portrait. Mikhail like Ivan was a wealth patron of the arts as well as being an avid collector of works by Van Gogh, Gaugin, Degas and Renoir. Serov’s portrait of Mikhail is a much sterner depiction. He stares out at us with a stern gaze which is somewhat unsettling. In the early 1900s Mikhail had built up a collection of eighty-three paintings by Russian and West European artists. The highlight of his collection were works by Maurice Denis, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Vincent Van Gogh. It was Mikhail who brought these artists to the attention of his brother Ivan and another art collector by the name of Sergei Shchukin. Mikhail sadly died in 1903, and sixty paintings from his collection were bequeathed to the Tretyakov Gallery.

In complete contrast to this disconcerting portrait of Mikhail, that same year Serov painted a wonderful portrait of Mikhail’s son, Mika. It all came about when Serov and Mikhail Morozov were sitting talking when Mika bounded into the room, full of energy, full of life. Mika’s childish innocence amazed Serov and he agreed to carry out a portrait of the young boy. Serov’s problem with carrying out such a portrait was how to get the child to sit still. Serov’s solution to this problem was to start telling Mika Russian fairy tales and Mika listened with his eyes wide-open and that is what we see in this poignant portrait by Serov. In return to hearing the stories, Mika also retold the tales back to Serov, which he had heard from his nanny and so with the story telling continuing, the portrait was completed.

My final set of portraits completed by Valentin Serov features Henrietta Leopoldovna Girshman, a lady who was once referred to as the most beautiful woman in Russia. From 1904 Serov’s favourite model was Henrietta Leopoldovna Girshman. She was the hostess of a famous Moscow salon as well as being the wife of the prominent industrialist, art collector and patron of arts, Vladimir Girshman. Strikingly beautiful, Henrietta inspired several well-known Russian artists to paint her portrait. Serov’s 1904 gouache on cardboard Portrait of Henrietta features the subject sitting with its flowing lines associated with the modernist style. Yet Serov was not satisfied with this drawing and attempted to destroy it.

Valentin Serov’s 1906 portrait of her in her boudoir hangs at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Henrietta stares confidently out at us in the knowledge that she has attained her status as the influential centre of Russian culture. Serov mimics Velazquez’s “Las Meninas” with his image appearing in the reflection of himself at the right side of the mirror.

Henrietta Girshman and her husband, Vladimir nurtured cultural exchanges and initiatives by organizing art-oriented programs and meetings and by founding the Society of Free Esthetics in 1907. They often opened their home for recitals, poetry readings and theatrical improvisations and welcomed such friends as Valentin Serov, Sergei Diaghilev, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Maxim Gorky.

Of all the paintings featuring Henrietta, Serov’s favourite was his final portrait of her, an oval, which he completed in 1911. The 1917 Russian Revolution forced the Girshmans into exile. Their house was confiscated and its contents and their art collection were nationalized. They eventually settled in Paris, and Henrietta revived her salon albeit on a much smaller scale.

Serov taught in the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1897 to 1909. He died in Moscow on December 5th 1911, from a form of angina that eventually led to cardiac arrest and heart failure due to severe complications. He was just forty-six years old. He was buried at the Donskoye Cemetery and later his remains exhumed and reburied at the Novodevichy Cemetery. A retrospective of his work was held at the Tretyakov Gallery in 2016 and it attracted record crowds.

In the middle ground we see the solitary figure of Christ on a rocky mound approaching the gathering. Behind him in the background is a wide plain and the distant mountains. His figure is small in comparison to the others but nevertheless stands out because of it being a lone figure. In the foreground of the picture there are a number of male figures of varying ages, some of whom are already undressed waiting to be baptised.

In the middle ground we see the solitary figure of Christ on a rocky mound approaching the gathering. Behind him in the background is a wide plain and the distant mountains. His figure is small in comparison to the others but nevertheless stands out because of it being a lone figure. In the foreground of the picture there are a number of male figures of varying ages, some of whom are already undressed waiting to be baptised.

The founder of the Surrealist movement was the French poet and critic André Breton who launched the movement by publishing the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 and led the group till his death in 1966. Surrealist artists find magical enchantment and enigmatic beauty in the unexpected and the strange, the overlooked and the eccentric. In a way, it is a belligerent dismissal of conservative, if somewhat conformist, artistic values. The depictions in the Surrealist paintings are startling often colourful. In some ways they are mesmerising and one wonders what was going through the mind of the painter when they put their ideas on canvas or wood. My featured artist today is French and she was considered to be one of the leading twentieth century French Surrealist painters. Let me introduce you to Agnès Boulloche.

The founder of the Surrealist movement was the French poet and critic André Breton who launched the movement by publishing the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 and led the group till his death in 1966. Surrealist artists find magical enchantment and enigmatic beauty in the unexpected and the strange, the overlooked and the eccentric. In a way, it is a belligerent dismissal of conservative, if somewhat conformist, artistic values. The depictions in the Surrealist paintings are startling often colourful. In some ways they are mesmerising and one wonders what was going through the mind of the painter when they put their ideas on canvas or wood. My featured artist today is French and she was considered to be one of the leading twentieth century French Surrealist painters. Let me introduce you to Agnès Boulloche.

Another painting which came from his many sketches he made whilst in France, was one he sketched whilst on his journey back home. It was entitled Fishmarket on the Beach at Boulogne and Crome completed it in 1820.

Another painting which came from his many sketches he made whilst in France, was one he sketched whilst on his journey back home. It was entitled Fishmarket on the Beach at Boulogne and Crome completed it in 1820.

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.

The sheer size of this work, 304 x 505cms (119 x 199 in) is breathtaking.

Curinier in his 1899 Dictionnaire National Des Contemporains (National dictionary of present-day people) wrote of Luigi Loir:

Curinier in his 1899 Dictionnaire National Des Contemporains (National dictionary of present-day people) wrote of Luigi Loir:

In one of the volumes of Figures Contemporaines: Tirées De L’album Mariani, illustrated biographies of famous contemporary characters from 1894 to 1925, Luigi Loir’s relationship with Paris as depicted in his art was explained:

In one of the volumes of Figures Contemporaines: Tirées De L’album Mariani, illustrated biographies of famous contemporary characters from 1894 to 1925, Luigi Loir’s relationship with Paris as depicted in his art was explained:

While her father was a prolific artist, his daughter’s artistic output was much more meagre for one has to remember she was a wife and a mother. She was married at the age of twenty-one and became a mother when she was twenty-two and so the output of her work was severely restricted by her responsibilities as a wife and a mother.

While her father was a prolific artist, his daughter’s artistic output was much more meagre for one has to remember she was a wife and a mother. She was married at the age of twenty-one and became a mother when she was twenty-two and so the output of her work was severely restricted by her responsibilities as a wife and a mother.

The mural on the north wall, to the left of the Hearing Room shows King John of England sealing and granting Magna Charta (the Great Charter) in June 1215 on the banks of the Thames River at the meadow called Runnymeade. His reluctance to grant the Charter is shown by his posture and sullen countenance. But he had no choice. The barons and churchmen led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, forced him to recognize principles that have developed into the liberties we enjoy today. King John, out of avarice, greed or revenge, had in the past seized the lands of noblemen, destroyed their castles and imprisoned them without legal cause. As a result, the noblemen united against the king. Most of the articles in Magna Charta dealt with feudal tenures, but many other rights were also included.

The mural on the north wall, to the left of the Hearing Room shows King John of England sealing and granting Magna Charta (the Great Charter) in June 1215 on the banks of the Thames River at the meadow called Runnymeade. His reluctance to grant the Charter is shown by his posture and sullen countenance. But he had no choice. The barons and churchmen led by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, forced him to recognize principles that have developed into the liberties we enjoy today. King John, out of avarice, greed or revenge, had in the past seized the lands of noblemen, destroyed their castles and imprisoned them without legal cause. As a result, the noblemen united against the king. Most of the articles in Magna Charta dealt with feudal tenures, but many other rights were also included. The mural on the west wall over the entrance to the Hearing Room depicts an incident in the reign of Caesar Augustus Octavius. The Roman writer Seutonious tells of Scutarious, a Roman legionnaire who was being tried for an offense before the judges seated in the background. The legionnaire called on Caesar to represent him, saying: “I fought for you when you needed me, now I need you.” Caesar responded by agreeing to represent Scutarious. Caesar is shown reclining on his litter borne by his servants. Seutonious does not tell us the outcome of the trial but leaves us to surmise that with such a counsellor he undoubtedly prevailed. The mural represents Roman civil law, which is set forth in codes or statutes, in contrast to English common law, which is based not on a written code but on ancient customs and usages and the judgments and decrees of the courts which follow such customs and usages.

The mural on the west wall over the entrance to the Hearing Room depicts an incident in the reign of Caesar Augustus Octavius. The Roman writer Seutonious tells of Scutarious, a Roman legionnaire who was being tried for an offense before the judges seated in the background. The legionnaire called on Caesar to represent him, saying: “I fought for you when you needed me, now I need you.” Caesar responded by agreeing to represent Scutarious. Caesar is shown reclining on his litter borne by his servants. Seutonious does not tell us the outcome of the trial but leaves us to surmise that with such a counsellor he undoubtedly prevailed. The mural represents Roman civil law, which is set forth in codes or statutes, in contrast to English common law, which is based not on a written code but on ancient customs and usages and the judgments and decrees of the courts which follow such customs and usages. The mural on the south wall portrays the trial of Chief Oshkosh of the Menominees for the slaying of a member of another tribe who had killed a Menominee in a hunting accident. It was shown that under Menominee custom, relatives of a slain member could kill his slayer. Judge James Duane Doty held that in this case territorial law did not apply. He stated:

The mural on the south wall portrays the trial of Chief Oshkosh of the Menominees for the slaying of a member of another tribe who had killed a Menominee in a hunting accident. It was shown that under Menominee custom, relatives of a slain member could kill his slayer. Judge James Duane Doty held that in this case territorial law did not apply. He stated: The fourth mural, which is actually the first one that is visible on making an entrance to the Supreme Court Room, and is Albert Herter’s rendition of the signing of the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. George Washington is shown presiding. On the left, Benjamin Franklin is easily recognizable. On the right, James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” is shown with his cloak on his arm. Although he was in France at the time, Thomas Jefferson was painted into the mural because of his great influence on the principles of the Constitution. The painting hangs above the place where the seven member Wisconsin Supreme Court sit to hand down their decisions. The mural’s position above the bench is symbolic that the Supreme Court operates under its aegis and is subject to its constraints. The United States Constitution has served us well for more than 200 years. This mural shows our indebtedness to federal law.

The fourth mural, which is actually the first one that is visible on making an entrance to the Supreme Court Room, and is Albert Herter’s rendition of the signing of the Constitution at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. George Washington is shown presiding. On the left, Benjamin Franklin is easily recognizable. On the right, James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” is shown with his cloak on his arm. Although he was in France at the time, Thomas Jefferson was painted into the mural because of his great influence on the principles of the Constitution. The painting hangs above the place where the seven member Wisconsin Supreme Court sit to hand down their decisions. The mural’s position above the bench is symbolic that the Supreme Court operates under its aegis and is subject to its constraints. The United States Constitution has served us well for more than 200 years. This mural shows our indebtedness to federal law.

The mural on the left was a scene from the court case against a local magistrate, Samuel Sewall. In 1692 a small group of men and women of Salem were arrested for bewitching their neighbours. Samuel Sewall, a local magistrate, was a member of the court that ultimately sentenced nineteen people to be hanged. The tragedy was realised several months later: those still being held were released. In the mural, Sewall is seen standing in Old South Church in Boston with his head bowed as his confession and prayers for pardon are read aloud.

The mural on the left was a scene from the court case against a local magistrate, Samuel Sewall. In 1692 a small group of men and women of Salem were arrested for bewitching their neighbours. Samuel Sewall, a local magistrate, was a member of the court that ultimately sentenced nineteen people to be hanged. The tragedy was realised several months later: those still being held were released. In the mural, Sewall is seen standing in Old South Church in Boston with his head bowed as his confession and prayers for pardon are read aloud.

António was born in Porto in a neighbourhood which was populated by many artists and it was with him mixing in their company that he fell in love with art. He studied art at university and achieved a degree in Fine Arts. He later taught art and eventually became a professional artist. He moved to the Algarve in 2009 and founded his studio in Silves, which backs on to the Silves railway station. He says that the name he gave the studio, O Templo do Tempo, is his perception of art because he always felt that when something is truly art, it belongs to the past, present, and future – art, he says, is timeless.

António was born in Porto in a neighbourhood which was populated by many artists and it was with him mixing in their company that he fell in love with art. He studied art at university and achieved a degree in Fine Arts. He later taught art and eventually became a professional artist. He moved to the Algarve in 2009 and founded his studio in Silves, which backs on to the Silves railway station. He says that the name he gave the studio, O Templo do Tempo, is his perception of art because he always felt that when something is truly art, it belongs to the past, present, and future – art, he says, is timeless.

A few months ago when I was in Moscow I was fortunate to visit the Tretyakov Museum and look at their wonderful collection. I started that series of blogs by talking about the founder of the Museum before looking at some of the works in the collection. Whilst in the Algarve I took a train up to Lisbon and spent three days in the capital. During that time I visited the large Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in the heart of the city. It was an incredible museum in a tranquil and beautiful setting in the heart of the Portugeuse capital. So who is Calouste Gulbenkian?

A few months ago when I was in Moscow I was fortunate to visit the Tretyakov Museum and look at their wonderful collection. I started that series of blogs by talking about the founder of the Museum before looking at some of the works in the collection. Whilst in the Algarve I took a train up to Lisbon and spent three days in the capital. During that time I visited the large Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in the heart of the city. It was an incredible museum in a tranquil and beautiful setting in the heart of the Portugeuse capital. So who is Calouste Gulbenkian?

In December 1887 Calouste returned home to Istanbul. In September 1888 he travelled to Eastern Europe and the Azerbaijan capital of Baku via Batumi and Tiblisi, to learn about the Russian oil industry. Three years later in 1891, he published a book about his month-long journey of discovery entitled La Transcaucasie et la péninsule d’Apchéron; souvenirs de voyage (“Transcaucasia and the Absheron Peninsular – Memoirs of a Journey”) and parts of it appeared in the Revue des deux Mondes, the French language monthly literary, cultural and political affairs magazine.

In December 1887 Calouste returned home to Istanbul. In September 1888 he travelled to Eastern Europe and the Azerbaijan capital of Baku via Batumi and Tiblisi, to learn about the Russian oil industry. Three years later in 1891, he published a book about his month-long journey of discovery entitled La Transcaucasie et la péninsule d’Apchéron; souvenirs de voyage (“Transcaucasia and the Absheron Peninsular – Memoirs of a Journey”) and parts of it appeared in the Revue des deux Mondes, the French language monthly literary, cultural and political affairs magazine.