William McTaggart’s art was likened to Impressionism and yet he was a forerunner of that genre. He was a pioneer of Impressionism before it was given a label. It is true that he was fascinated with nature and man’s relationship with it, and he endeavoured to capture aspects such as the fleeting effects of light on water. He also, like the Impressionists, liked to paint en plein air. This aspect of his work was discussed in an early edition of the Art Journal:

“…A Scottish Impressionist”, points out that “before the term had been imported from France and Monet and the rest had formulated their creed, Mr McTaggart had evolved for himself a method and style not unlike what they ultimately achieved, but exceeding it in suggestion, significance, and beauty…”

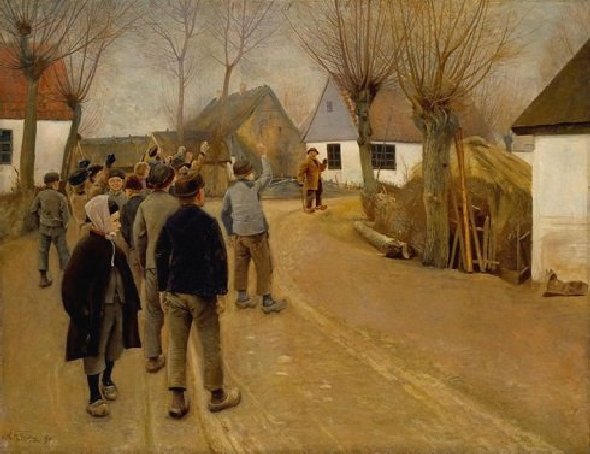

After the period when McTaggart depicted idyllic scenes populated with young children he turned to landscape and seascape work, the latter being motivated by the love of the sea as a child when he lived close to Machrihanish and the storm ravaged Atlantic coast, often battered by the great and unforgiving ocean. William McTaggart would visit Machrihanish and paint the bay and the vast expanse of the sea. He would paint en plein air at different times of the day capturing the understated appeal of the waves as they rolled towards the long continuous stretch of seashore under sunlight with the white streaks of the breaking waves. Other works depicted the rocky shoreline with just a hint of colour. In his works such as Machrihanish Bay, his depiction brings out a feeling not just the powerfulness of the sea but the aloneness, two feelings which he recognised would be in the mind of the fishing folk as they went on their daily voyage.

His 1890 painting entitled The Storm emphasised the darker side of the sea and the perils waiting for those who chose to underestimate or defy it. As we look at the painting, we can almost hear the howling wind and the sound of the crashing waves upon the rocky foreshore.

It has to be noted that in McTaggart’s later paintings, details became secondary to his desire to depict his personal consciousness of nature and the life around him and the effect of differing light on what he saw before him. An example of this is his early 1890’s painting entitled The Fishing Fleet Setting Out. We see the children of the fishermen in the foreground almost camouflaged by the rocks. They are playing in the rock pools. In the far distance we see the fishing fleet setting out to sea. A detailed depiction of the children was not important to McTaggart who was more interested in the ever-changing state of the sea and the weather. He has used a pink/cocoa coloured ground which enhances and gives a hazy warmth to the scene.

McTaggart painted numerous seascapes featuring the waters around southern Kintyre. In 1895 he completed a work entitled The Coming of St Columba. St Columba had left Ireland on a missionary voyage to Scotland in 563AD. He and twelve travelling companions travelled across the Irish sea in a wicker boat known as a currach which was covered with leather. Legend has it that he landed on the south of Kintyre, close to the small village of Southend before journeying onwards north to the Isle of Iona. In McTaggart’s depiction of the arrival of the saint he has used The Gauldrons instead, as the setting for the work. The Gauldrons (Scottish Gaelic: Innean nan Gailleann) meaning “Bay of Storms” is a bay facing the Atlantic Ocean in the village of Machrihanish in Argyll, on the west coast of Scotland, a short distance north of the tip of the Mull of Kintyre. The figures and boats were added in the studio after the landscape was completed

In 1902, he completed another seascape entitled And All the Choral Waters Sang which comes from a line of verse from the famous Victorian poet, Algernon Charles Swinburne’s poem, At a Months End:

“…Hardly we saw the high moon hanging,

Heard hardly through the windy night

Far waters ringing, low reefs clanging,

Under wan skies and waste white light.

With chafe and change of surges chiming,

The clashing channels rocked and rang

Large music, wave to wild wave timing,

And all the choral water sang…”

The depiction evokes the music of the crashing Atlantic waves on Machrihanish beach. McTaggart’s son-in-law, James Caw, who had married William’s daughter, Anne, said that the work was painted entirely in the open at Machrihanish in June 1902. In his book, William McTaggart, R.S.A., V.P.R.S.W.; a biography and an appreciation, Caw writes about this work:

“…Both breeze and sunshine pervade the masterpiece, to which Swinburne’s splendidly descriptive line, “And all the Choral Waters sang,” was given as title. Yet, while the mighty music of great waves breaking in many rhythmic chords of thundering surf upon the Atlantic shore is recreated to the imagination by the artist’s wizardry of line and colour and design, one feels as keenly the “Light that leaps and runs and revels through the springing flames of spray.” Looking north-west, the radiant early afternoon sunshine of June falls upon the ordered on-rush of these charging regiments of rearing and plunging white horses sweeping into the long curving bay, and raises their white foaming manes and flying silver tails to a brilliance greater than that of sun-illumined snow. And, between the gleaming lines of racing white, the wind-swept sky throws reflections of vivid changing blues, which, mingling with the lustrous greens amid the leaping waves and the rosy purples and tawnies afloat in the shoreward shooting ripples, make a wonderful and potent colour harmony. Words, however, are woefully inadequate to convey any real impression of this splendid picture — this great sea symphony in colour and light and movement. And, pathetic though “a symphony transposed for the piano” may be, reproduction of such a picture is even more disappointing…”

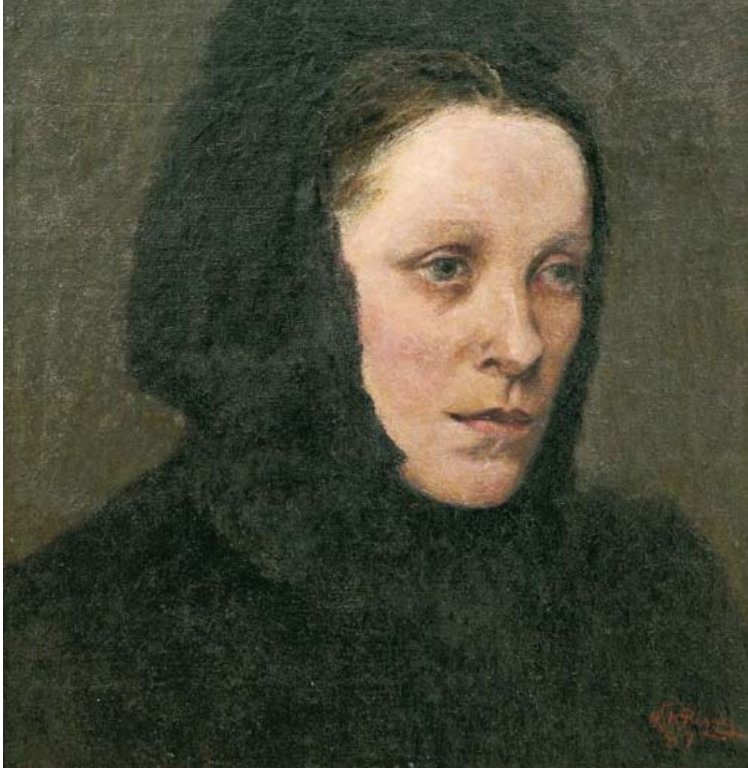

William McTaggart suffered two great losses in 1884. In November, his mother died, aged 80. She had been living in Glasgow but had in her latter years returned to Campbeltown. William had been greatly devoted to his mother and her death had greatly affected him. During the few days he and his wife had been at Campbeltown his wife’s health, which had been poor, deteriorated. On returning home they consulted her doctor who recommended an immediate operation and this was carried out immediately. Sadly, Mrs McTaggart never recovered and on December 15th 1884 she died, aged 47. William and his children were devastated. His eldest daughter, Jean, would not let him out of her sight even when he was trying to court his future second wife, Marjorie Henderson.

In 1886 McTaggart completed a portrait of his eldest daughter, Jean. It was entitled Belle. She stands before us in a red frock with a lace collar. The painting was owned by Jean’s sisters who later bequeathed it to the National Galleries Scotland in 1991.

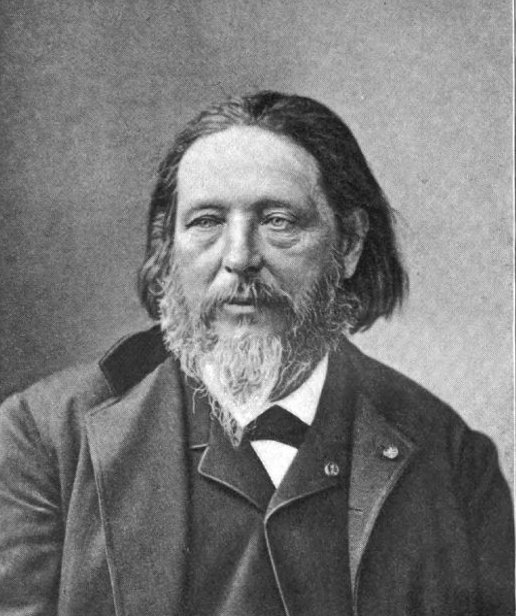

On April 6th 1886, William McTaggart married Marjory Henderson, who was the eldest daughter of Joseph Henderson, a well-known Glasgow artist, and who, despite their age difference, had forged a close relationship with McTaggart’s eldest daughter, Jean. William was fifty-one and Marjory was thirty-years of age. Unfortunately, this large difference in age led to a certain amount of unwelcoming gossip. However, this second marriage proved an incredibly happy one and, importantly, his new wife was accepted by all the children from his first marriage. William and Marjorie went on to have a further nine children. This harmonious atmosphere at home was so important to his progression as an artist

By the end of the 1880’s William Taggart’s paintings were selling so well that he started to refuse commissions which meant he was told what to paint. By doing this he could choose what to depict on his canvases, such as seascapes and landscapes of his choice. In 1889 all his works held by the art dealer, Dowells, were put up for sale and a total of £4000 was realised, an amazing figure for the time. In the May of that year he moved from his Edinburgh studio and went to live at Dean Park, Broomieknowe, on the outskirts of Lasswade, Midlothian, some ten miles south east of the Scottish capital. It was here he built himself a small studio which would last him six years until 1895, at which time, he built a much larger studio/gallery. He was sixty years old and finally he was able to relax and enjoy semi-retirement. He lived in an uncomplicated and undemanding manner and often welcomed young aspiring painters to his studio. He was always supportive and had words of encouragement for them. William McTaggart died of heart failure, at his home in Dean Park, Broomieknowe, Lasswade on the afternoon of April 2nd 1910 at the age of 75. He had been very poorly during the previous winter but it was still a shock to his family when he suddenly died. He had spent the last twenty years of his life at his home, Dean Park and although it was somewhat isolated from the artistic hubbub of Edinburgh, William was just pleased to have the company of his large family and visiting friends.

His funeral was held on April 5th at Echo Bank Cemetery in Newington, Edinburgh and was attended by a large crowd with a procession of some twenty mourning coaches leaving Bonnyrigg for the short journey to Edinburgh. He lies with both his first and second wives: Mary Holmes and Marjory Henderson. Three of his children who died in infancy and are buried with him. His daughter, Annie Mary who married the art historian Sir James Caw, lies alongside. Joseph’s sons John Henderson and Joseph Morris Henderson also became painters as did his fifth daughter from his second marriage, Eliza (Betty) McTaggart.

A good deal of information for this and the previous blog came from the Bonnyrigg Lasswade Local History website:

bonnyrigglasswadelocalhistory.org/

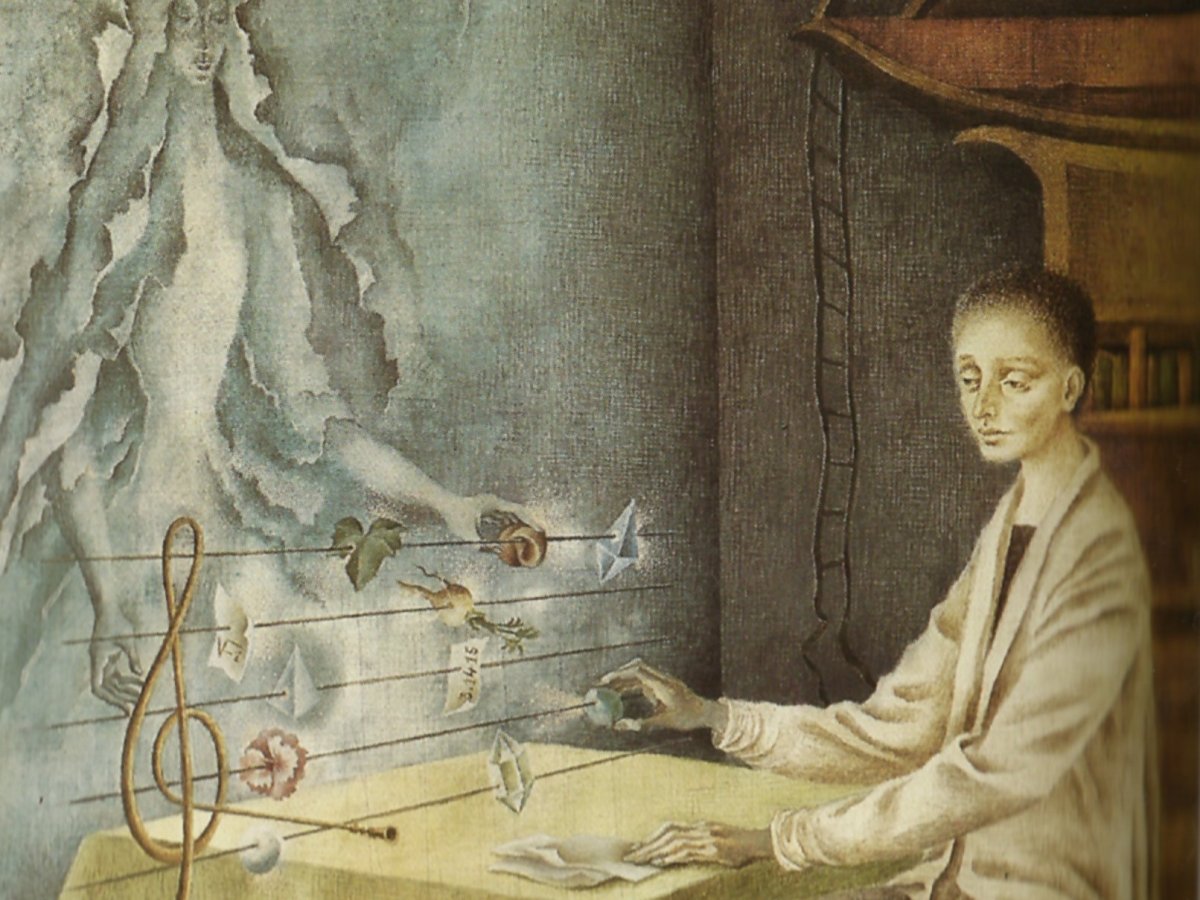

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”

In her early days in Mexico, Remedios did few paintings and spent most of her time writing. She and Leonora Carrington would write fairy tales, collaborated on a play, invented Surrealistic potions and recipes, and influenced each other’s work. The two women, together with another of their friends, the photographer Kati Horna became known as “the three witches”

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

In 1958, Remedios Varo participated in the First Salon of Women’s Art at the Galerías Excelsior of Mexico, together with Leonora Carrington, Alice Rahon, Bridget Bate Tichenor and other contemporary women painters of her era. Remedios submitted two of her works, Harmony and Be Brief, and won the first prize of 3,000 pesos.

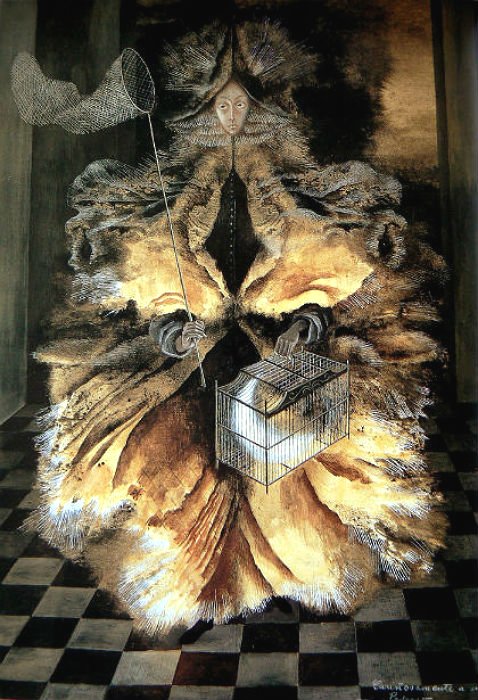

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

If you look closely at the chest cavity of the figure you will detect the circle of yin-yang, the Chinese symbol that similarly represents the balance of opposites. The face of the figure is one of calmness and serenity and suggests inner harmony and balance.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

In 1963 Remedios suffered some health problems. She had complained of a shortage of breath when climbing stairs. She had a history of chronic gastric problems and was known to drink excessive amounts of coffee as well as being a heavy smoker. She was checked out for heart problems but was given a clean bill of health. The state of her mental health was open to doubt. Some of her friends said she was bubbly and full of life whist others said she had told them that she was depressed and did not know whether she could carry on with life. Walter Gruen, her husband, remembered the devastating afternoon of October 8th 1963, saying that he and Remedios had lunched with their friend Roger Cossio who had come to buy Varo’s painting, The Lovers. Gruen said his wife was happily explaining the details of the work to the buyer. With lunch over Cossio left and Gruen returned to his Sala Margolin shop across from their house to do some work. Shortly after, their Indian maid rushed into Gruen’s shop to tell him that Remedios was very ill. Gruen rushed home to find his wife complaining of chest pains. Gruen was unable to contact a doctor so left Remedios and went into the next room to consult some medical books. When he returned to his wife, he found that she had died.

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

The third of the Red Rose Girls was Jessie Willcox Smith. She became one of the most prominent female illustrators in the United States, during the celebrated ‘Golden Age of Illustration‘. Jessie was the eldest of the trio, born in the Mount Airy neighbourhood of Philadelphia, on September 6th 1863, the youngest of four children. She was the youngest daughter of Charles Henry Smith, an investment broker, and Katherine DeWitt Willcox Smith. Her father’s profession as an “investment broker” is often questioned as although there was an investment brokerage called Charles H. Smith in Philadelphia there is no record of it being run by anybody from Jessie Smith’s family. In the 1880 city census, Jessie’s father’s occupation was detailed as a machinery salesman. Jessie’s family was a middle-class family who always managed to make ends meet. Her family originally came from New York and only moved to Philadelphia just prior to Jessie’s birth. Despite not being part of the elite Philadelphia society, her family could trace their routes back to an old New England lineage. Jessie, like her siblings, were instructed in the conventional social graces which were considered a necessity for progression in Victorian society. It should be noted that there were no artists within the family and so as a youngster, painting and drawing were not of great importance to her. Instead her enjoyment was gained from music and reading. Jessie attended the Quaker Friends Central School in Philadelphia and when she was sixteen, she was sent to Cincinnati, Ohio to live with her cousins and finish her education.

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.

Jessie Willcox Smith graduated from the Academy in June 1888. She looked back on her time at the Academy with a certain amount of disappointment. Although her technique had improved, she had hoped to be part of an artistic community in which artistic collaboration would be present but instead she found dissention, scandal and in the wake of the Eakins’ scandal, institutionalized isolation. Jessie talked very little about her time at the Academy. It had been a turbulent time and she had hated conflict as it unnerved her and made her extremely distressed. This desperation to avoid any kind of conflict in her personal and professional life revealed itself in her idealistic and often blissful paintings. Jessie wanted to believe life was just a period of happiness.

He completed Legend and Stories of King Arthur in 1903. The book contains a compilation of various stories, adapted by Pyle, regarding the legendary King Arthur of Britain and select Knights of the Round Table. Pyle’s novel begins with King Arthur in his youth and continues through numerous tales of bravery, romance, battle, and knighthood.

He completed Legend and Stories of King Arthur in 1903. The book contains a compilation of various stories, adapted by Pyle, regarding the legendary King Arthur of Britain and select Knights of the Round Table. Pyle’s novel begins with King Arthur in his youth and continues through numerous tales of bravery, romance, battle, and knighthood.